Two Theories of Practice for Science Teaching

By Felicia Moore Mensah

A s we know, our society—hence, our classrooms—are becoming increasingly diverse in terms of racial, ethnic, cultural, economic, and religious diversity. Much of this diversity brings challenges in meeting the needs of all our students. In the current situation of the COVID-19 pandemic, educational, health, and racial disparities are magnified and brought into the light more than ever. As we think about what to teach during a global pandemic, questions regarding the curriculum and instruction also come into greater focus. What kinds of approaches are used to raise critical consciousness and cultural connections in the content that we teach to our students? Several approaches have been used that focus on student diversity ( Mensah 2011 ), and given the challenges of remote emergency teaching, these approaches will not address every circumstance, but they do offer assurance that teaching and learning remain high goals for all our students. Approaches that foreground, support, and value student culture and identity are critically important, particularly now.

Gloria Ladson-Billings and Geneva Gay are two prominent figures in education whose work on culturally relevant teaching and culturally responsive teaching, respectively, has been very influential in the work I do supporting student learning and academic success for students of diverse cultural and linguistic backgrounds and the teachers who teach them. The two frameworks have been used extensively across multiple fields and subject areas, including science education, preservice education, teacher professional development, curriculum development, and student learning. Due to the familiarity of these frameworks in education, it is fitting that culturally relevant and culturally responsive teaching are highlighted in this special issue of Science and Children. The two frameworks come from different philosophical orientations, while they also share common goals. Thus, it is worth laying some foundational knowledge of them while giving attention that both are focused on culture, race, equity, and the success of students traditionally marginalized in the educational system.

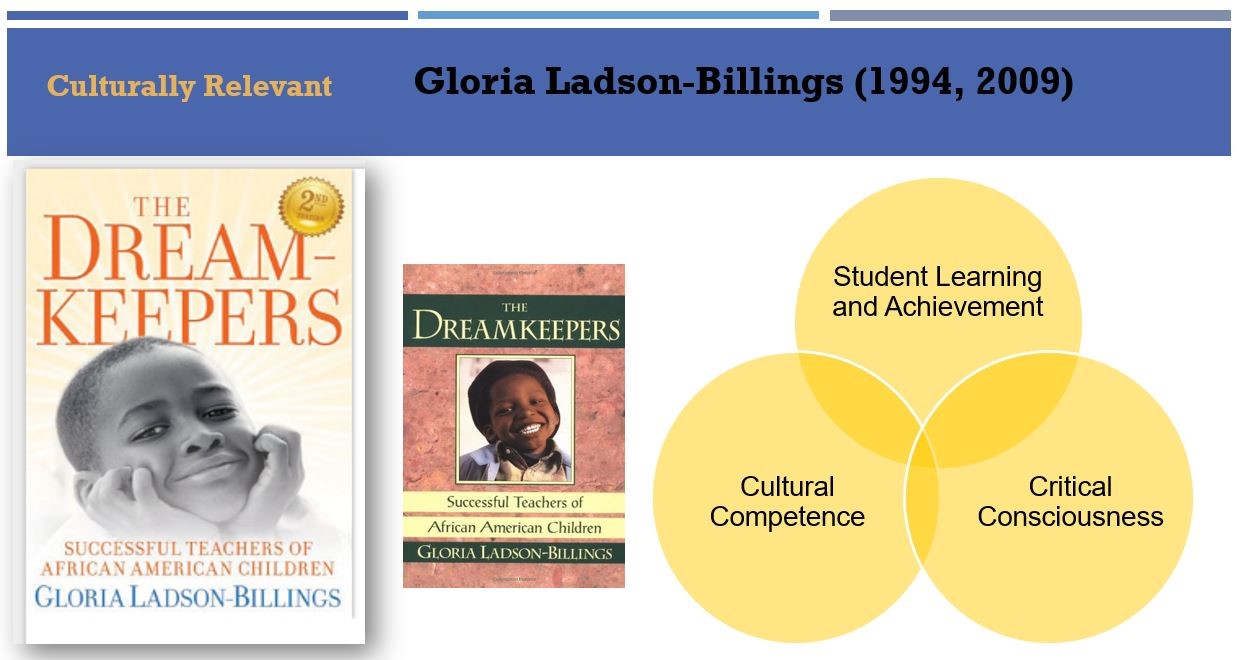

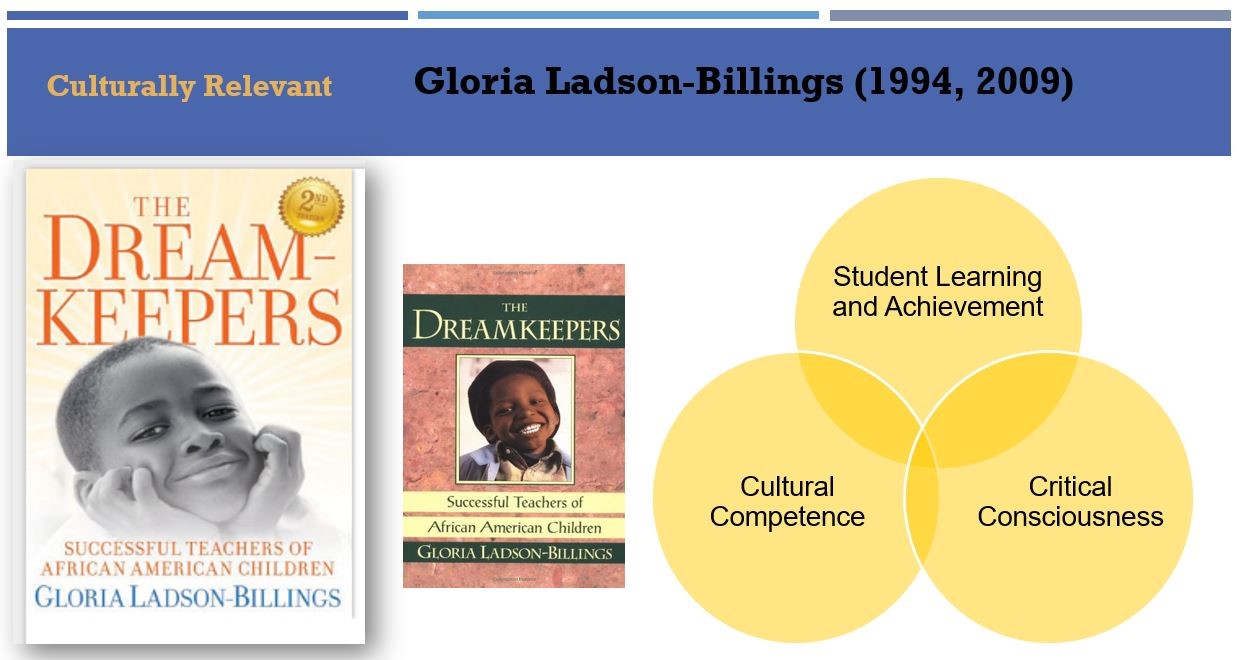

First, the theoretical and practical knowledge that helped to form a theory of culturally relevant teaching originated from Ladson-Billings’ work to capture the pedagogical excellence of successful teachers of Black students. From conducting ethnographic interviews with teachers, viewing videos of classroom teaching, and working with teachers who also served as researchers in their classrooms, Ladson-Billings began formulating notions of culturally relevant teaching. In her seminal book The Dreamkeepers (2009), she wanted to capture and address student achievement and challenge deficit views about African American students and their academic success. Ladson-Billings defined culturally relevant pedagogy (or culturally relevant teaching) as a “theoretical model that not only addresses student achievement but also helps students to accept and affirm their cultural identity while developing critical perspectives that challenge inequities that schools (and other institutions) perpetuate” (1995, p. 469). Culturally relevant teaching is a way to “empower students intellectually, socially, emotionally, and politically by using cultural referents to impart knowledge, skills, and attitudes” (1994, p. 18). Each proposition supports the idea that “culturally relevant pedagogy is designed to problematize teaching and encourage teachers to ask about the nature of the student-teacher relationship, the curriculum, schooling, and society” ( Ladson-Billings, 1995a , p. 469). The nature of student-teacher relationships cannot be addressed without teachers getting to know the multiple identities of their students, as students are raced, classed, and gendered individuals, for example, and bring these multiple identities to the classroom. Science and curriculum can and should connect these identities. Furthermore, a teacher who enacts culturally relevant pedagogy teaches and believes that students of all racial, ethnic, and cultural backgrounds can achieve academically; the teacher acknowledges that students have numerous ways to demonstrate cultural competence; and that the teacher as well as the student understands and critiques how society and education work in unjust ways (Ladson-Billings 1995). Culturally relevant pedagogy is based on three propositions: academic success, cultural competence, and sociopolitical consciousness (Figure 1). Thus, she argues that culturally relevant pedagogy is “just good teaching” (Ladson-Billings 1995), yet it is so rarely happening in our science classrooms.

In slight contrast to the origins of culturally relevant teaching, Geneva Gay (2018) offered a broader conception of culturally responsive teaching. Gay in essence argued for a “paradigmatic shift in the pedagogy used with non-middle-class, non-European American students in U.S. schools. This is a call for the widespread implementation of culturally responsive teaching” (p. 25) that addresses the multiculturalism found among students in classrooms. Gay’s notions of culturally responsive teaching insist that a different pedagogical model is needed to improve the performance of underachieving students from various ethnic groups. Gay explains that culturally responsive teaching is both routine and radical:

“…routine because it does for Native American, Latino, Asian American, African American, and low-income students what traditional instructional ideologies and actions do for middle-class European Americans. That is, it filters curriculum content and teaching strategies through their cultural frames of reference to make the content more personally meaningful and easier to master. …radical because it makes explicit the previously implicit role of culture in teaching and learning, and it insists that educational institutions accept the legitimacy and viability of ethnic-group cultures in improving learning outcomes” (p. 32).

Essentially, culturally responsive teaching represents an assembling of various ideas, views, and explanations from many scholars. Therefore, culturally responsive teaching is defined as “using the cultural knowledge, prior experiences, frames of reference, and performance styles of ethnically diverse students to make learning encounters more relevant to and effective for them” (p. 36). Gay remarked that culturally responsive pedagogy has several characteristics that may link to learning outcomes for students—Culturally responsive teaching is validating, comprehensive, multidimensional, empowering, transformative, and emancipatory (Figure 2).

Collectively, culturally relevant pedagogy and culturally responsive teaching have many features in common and often are used interchangeably. Culturally relevant and culturally responsive pedagogies are concerned with liberatory teaching so that instruction and learners gain an understanding of the social, political, and historical knowledge to challenge and critique society and even what and how they are learning in the science classroom. Both aim to improve the academic success of Black, Brown, and Indigenous People of Color, referred to as BIPOC, while affirming their backgrounds, experiences, and identities. The science curriculum, content, and teaching strategies for BIPOC students of diverse cultural, ethnic, linguistic, and racial backgrounds should offer students multiple opportunities to access, gain, and use significant knowledge and skills while also inviting their knowledge and skills into science learning. Learning about students’ histories, making teaching and curriculum “culturally sustaining” to foster “linguistic, literate, and cultural pluralism” in schools is an aim of these approaches ( Paris 2012 , p. 93). There should be a mutual engagement of the learner, the content, and the curriculum to support the goals of culturally relevant and culturally responsive teaching in science classrooms.

Because students enter schools and classrooms with different degrees of experience, interests, knowledge, and supports from home, the idea of attending to these needs at once can be daunting for elementary science teachers. Students will not achieve academically if they are taught a watered-down science curriculum or taught a curriculum where they do not see themselves reflected in the curriculum or cannot see themselves as being successful in learning science. These views and practices only perpetuate deficit models of thinking and alienate students of diverse cultural, ethnic, and racial backgrounds. Over time, it will decrease their academic achievement and interest in science.

Rather than thinking that students from diverse cultural backgrounds are lacking and not capable of doing science, or having excuses for not providing an enriching and challenging science curriculum, teachers instead have to think of what students have in way of talents, multi-literacies, personal experiences, and interests, community knowledge, and family supports that enable them to engage in science culturally. How do you open science through your teaching practices, rather than making students assimilate into the culture of science that often neglects and alienates their full participation? Therefore, science teachers will have to critique, challenge, and change their pedagogies, thinking, and teaching practices to promote academic success in the ways that Ladson-Billings and Gay envision for students. The process of changing one’s mind requires seeing that students have funds of knowledge to support understanding of science and seeing how the science curriculum affords “ample cultural and cognitive resources” ( Moll, Amanti, Neff, and Gonzalez 1992 , p. 134) to promote active engagement and high academic standards. Culturally relevant and culturally responsive approaches to science teaching do this by taking advantage of the myriad opportunities to tailor and transform the science curriculum to meet the needs of students.

Culturally relevant pedagogy and culturally responsive teaching offer additional benefits for academic success in the science classroom that is not measured on tests. For example, due to the nature of science learning, students work together, teach each other, and share different perspectives as they engage in science. In the process, students also learn about cultural similarities and differences among themselves and how others think about science and use scientific knowledge. Curricula where racial, ethnic, and linguistic connections are made as students learn science makes science more meaningful and engaging. Second, the science classroom is an ideal setting for the development of positive identity exploration. This becomes important for girls’ engagement in science as well as students of color. Finally, in learning science, attention is given to responsibility, respect, and values in working collaboratively with others in solving problems, talking about ideas, and challenging ideas. These views connect to the inquiry-based practices we want students to develop in the science classroom. Teaching science in more culturally responsive ways includes linking students’ home experiences to the curriculum, embedding real-world problems in the curriculum, and using examples that connect to students’ experiences.

Furthermore, there is explicit teaching from an anti-racist lens. Science curriculum often does not attend to culturally relevant or responsive teaching in this way, so teachers find themselves having to modify, add, and adjust the curriculum they use. There is complementarity in meeting students’ needs, teaching science as inquiry, and incorporating three-dimensional teaching. Science educator Julie Brown ( 2017 ) conducted a study looking at culturally relevant and culturally responsive teaching and inquiry. She noted that students were more engaged when they posed and investigated their questions and when students engaged in science in meaningful and empowering ways. Culturally relevant and culturally responsive instruction should not feel like an add-on or be disjointed from the science curriculum but an intentionally planned part of the curriculum and instruction that happens in the classroom ( Rodriguez 2015 ). As teachers think about implementing culturally relevant or culturally responsive teaching in their instruction and curriculum, there is no “one-size-fits-all” way of doing so. Therefore, the creativity in developing science curriculum, while paying attention to the knowledge and identities of your students makes teaching in these ways creative and engaging for teachers and students.

The lessons in this special issue provide examples of culturally relevant or culturally responsive teaching that show the creativity of teachers as curriculum developers. The lessons allow students opportunities to build content knowledge that utilizes both Western science and Indigenous knowledge, community knowledge, and attends to their interests. It will of course take additional time to plan for this type of instruction yet collaborating with other teachers can support these practices and increase students’ science learning, engagement, and identities ( Mensah 2011 ). ●

Felicia Moore Mensah (fm2140@tc.columbia.edu) is a professor of science education and Vice Department Chair of Mathematics, Science and Technology at Teachers College, Columbia University in New York, City.