This guide will examine in detail a derivative contract called total return swaps, how they work, who they benefit, as well as the pros and cons of using them.

Best Crypto Exchange for Intermediate Traders and Investors

30+ million UserseToro is a multi-asset investment platform. The value of your investments may go up or down. Your capital is at risk. Don’t invest unless you’re prepared to lose all the money you invest. This is a high-risk investment and you should not expect to be protected if something goes wrong. Take 2 mins to learn more.

A swap is a derivative contract between two parties that constitutes the exchange of pre-agreed cash flows or liabilities from two different financial instruments. The cash flows are commonly determined using the notional principal amount (a predetermined dollar amount that each party pays interest to the other at specified intervals).

Each cash flow forms one leg (one part) of the swap. While one cash flow is typically fixed, the other is in motion and based on a standard interest rate, floating currency exchange rate (determined by supply and demand), or index price.

Swap contracts are used as risk hedging instruments to minimize the uncertainty of specific operations. In contrast to futures and options, swaps are traded over-the-counter and not on exchanges.

Additionally, swap counterparties are generally businesses and financial organizations, not individuals, because there is always a high counterparty (default) risk (the possibility of not meeting their required payments on their debt obligations) in swap contracts.

The institution that acts as a broker between two counterparties is called a swap bank. They facilitate the transactions by matching two ends of the deal and usually earn a slight premium from both parties.

Finally, swaps were established in the late 1980s and are thus a relatively new type of derivative. However, their simplicity and extensive applications make them one of the most frequently traded financial contracts.

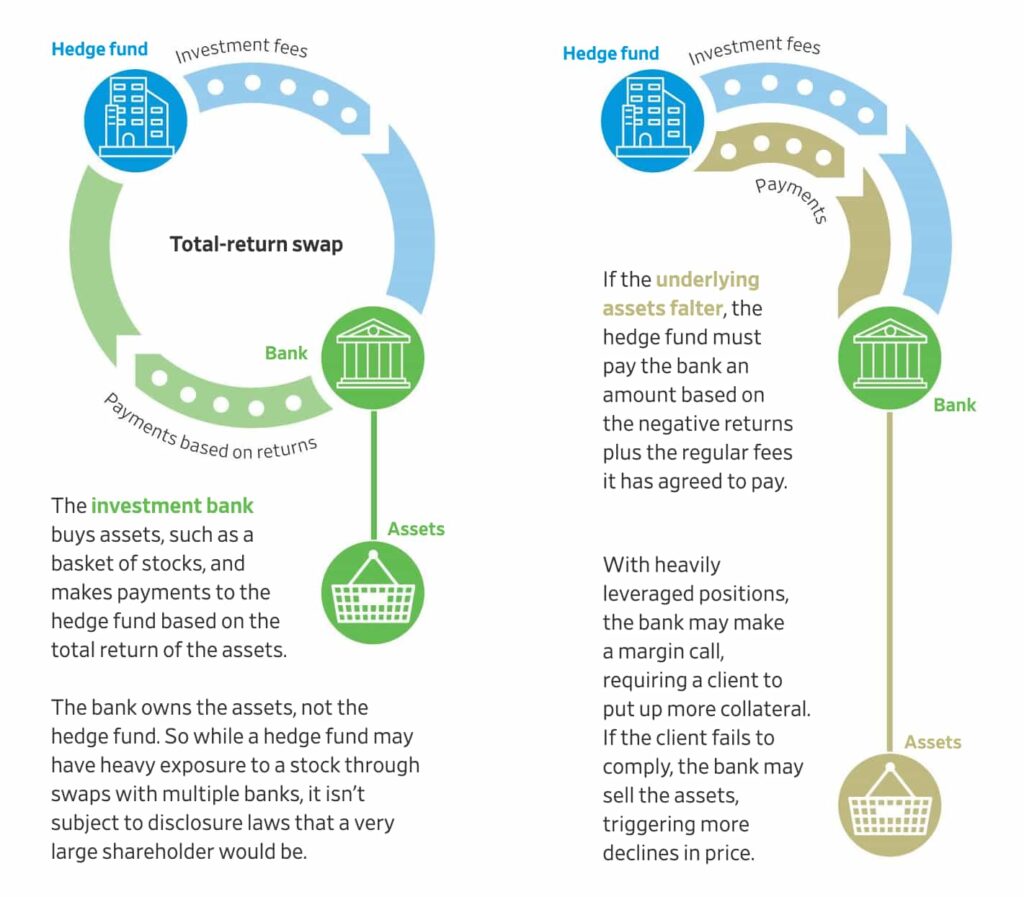

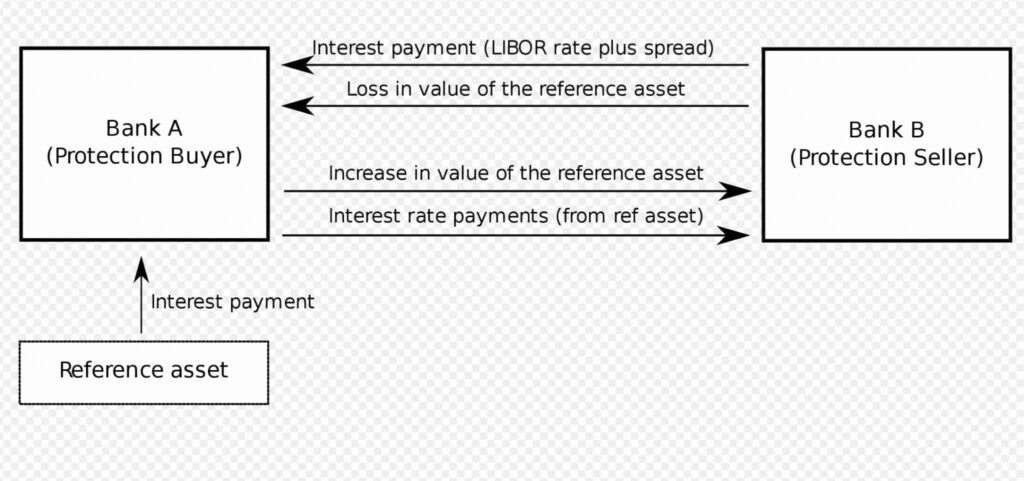

A total return swap (TRS) or total rate of return swap (TRORS), or cash-settled equity swap, is an agreement between two parties that constitutes the exchange of the return from a financial asset. In this contract, one party makes payments based on a set rate (either fixed or variable). In contrast, the other party makes payments based on the total return of an underlying asset, including both the income it generates and any capital gains.

The underlying asset, referred to as the reference asset, is typically a bond, equity index, or a basket of loans and is owned by the party receiving the set rate payment.

Total return swaps permit the party receiving the total return to profit from the reference asset without purchasing it. The receiving party also collects any income generated by the security but, in exchange, must pay the asset owner a set rate over the lifetime of the contract. Conversely, the asset owner expects to generate extra income on these assets and mitigate against capital losses.

Best Crypto Exchange for Intermediate Traders and Investors

30+ million UserseToro is a multi-asset investment platform. The value of your investments may go up or down. Your capital is at risk. Don’t invest unless you’re prepared to lose all the money you invest. This is a high-risk investment and you should not expect to be protected if something goes wrong. Take 2 mins to learn more.

Total return swaps are agreements brokered by Wall Street banks that enable users to bear the profits or losses of a portfolio of stocks or other assets in exchange for a fee.

Swaps also allow investors to take huge positions while putting limited funds upfront, essentially borrowing from the bank, allowing them to invest in assets without owning them. The two parties involved in a total return swap are the total return payer and the total return receiver.

In a TRS, the total return receiver collects any income generated by the asset and benefits if the asset’s price appreciates over the contract’s lifetime. In exchange, they must pay the asset owner (total return payer) the set rate over the lifetime of the swap.

If the asset’s price falls over the swap’s life, the party receiving the total return will be required to pay the security owner the amount the asset has decreased.

The owner bears no performance risk but takes on the credit exposure risk the receiver may be subject to, whereas the receiver assumes systematic and credit risks. For instance, if the asset price drops during the agreement’s lifetime, the receiver will pay the asset owner a fee equal to the amount of the asset price decline.

Total return swaps are generally used by investors who want to gain exposure to a specific security class without purchasing the underlying asset. In addition, these contracts can also be utilized to reduce the cost of holding an asset. Initially, it was created as a way for banks to hedge against default risk on a loan or group of loans.

The TRS market’s primary participants include large institutional investors such as investment banks, mutual funds, hedge funds, commercial banks, pension funds, funds of funds (a pooled fund that invests in other funds), private equity funds, and insurance companies, NGOs, and governments.

Moreover, special purpose vehicles (SPVs) such as Real estate investment trust (REITs) and bespoke collateralized debt obligation (finance product that is secured by a pool of loans and/or various assets) also participate in the market.

Typically, a hedge fund seeking exposure to particular securities pays for the exposure by leasing the assets from major institutional investors like investment banks and mutual funds. They hope to earn high returns from leasing the asset without purchasing it, thus leveraging their investment fully.

Conversely, the asset owner hopes to generate additional income in the form of LIBOR-based (the average interest rate at which global banks lend to one another) fees and agreed-upon spread to mitigate capital losses.

Let’s imagine two parties that enter into a one-year total return swap in which the first party receives a fixed margin of 2% in addition to the LIBOR (London Interbank Offered Rate). The second party receives the S&P 500 (Standard & Poor’s 500 Index) total return on a principal amount of $1 million.

After one year, LIBOR is at 2.5%, and the S&P 500 has appreciated by 18%. The owner pays the receiver 18% and acquires 4.5%, making the total for the receiver $135,000 ($1 million x (18% – 4.5%)).

In contrast, consider that the S&P 500 falls by 18% rather than appreciating. The first party would receive 18% in addition to the LIBOR rate plus the fixed margin, making the total for the owner $225,000 ($1 million x (18% + 4.5%)).

Bonds have become one of the most widespread underlying assets for total return swaps. A bond index total return swap is an agreement in which the total return swap is indexed to a series of bonds. This is an excellent structure compared to something like an equity and issues guaranteed income payments based on the underlying bonds’ coupon payments.

Moreover, the risk of the capital loss is limited in a bond. For bonds with good credit ratings, the absolute risk is mainly systemic and based on demand in the market for bonds in general. However, investors shouldn’t mistake this for the absence of risk. For example, if the sale price of bonds falls over the span of the contract, a bond indexed TRS can still lose money.

Finally, it allows the investor to access a bond market without buying and selling bonds, which are capital-demanding, long-term instruments.

In one of the most infamous cases using swaps, trader Bill Hwang, founder of Archegos Capital Management, rattled markets in March of 2021 when investors worldwide learned that his company had defaulted on loans used to create a $100 billion portfolio.

According to Bloomberg, this was one of the most spectacular failures in modern financial history, and no single individual has ever lost so much cash so quickly.

Archegos is estimated to have managed about $20 billion of its own money. However, its total positions that were wiped out approached $30 billion thanks to leveraging Archegos obtained from banks, all lost in the space of a week.

Because Hwang was using borrowed money and levering up his bets fivefold, his collapse left a trail of devastation. As banks dumped his holdings, stock prices plummeted. Credit Suisse Group AG, for example, one of Hwang’s lenders, lost $4.7 billion, and Nomura Holdings Inc. faced a loss of about $2 billion.

Using total return swaps instead of simply purchasing company shares provided two main benefits for Archegos. These derivatives enabled the company to boost its leverage, essentially owning more of an asset than its funds would have otherwise allowed. In addition, these swaps entitle investors like Hwang to maintain their anonymity.

Hwang also kept his lenders in the dark by trading via swap agreements. In a typical swap, a bank exposes its client to an underlying asset, such as a stock. While the client gains or loses from any price changes, the bank shows up in filings as the registered owner of the stock. That’s how Hwang was able to compile significant positions so quietly. And since the banks had details only of their dealings with him, they couldn’t know he was piling on leverage in the same assets via swaps with other banks.

One problem with stock picking at this scale is hedging, and Hwang never had an effective hedge. Many sophisticated stockpickers attempt to mitigate risk by balancing long positions with shorts on similar names and, as a result, making up some losses with profits if the market tanks.

Interestingly, if the stocks in his swap accounts rebounded, everyone would stay afloat. However, as soon as even one bank flinched and started selling, they’d all be exposed to plunging prices.

Recommended video: How to lose $20 billion in two days